Overview

In this post, we will talk about Arietta, the first piece in Edward Grieg’s Lyric Pieces, Op. 12. A convincing and sensitive performance of a piece comes from a deep understanding of the different aspects in theory, history, and technique. In this post, we will focus on the harmonic and theoretical context, and some teaching strategies to achieve melodic and harmonic lyricism. At the end of this post is a five-minute teaching video of some demonstration of these points.

History and Background of Arietta

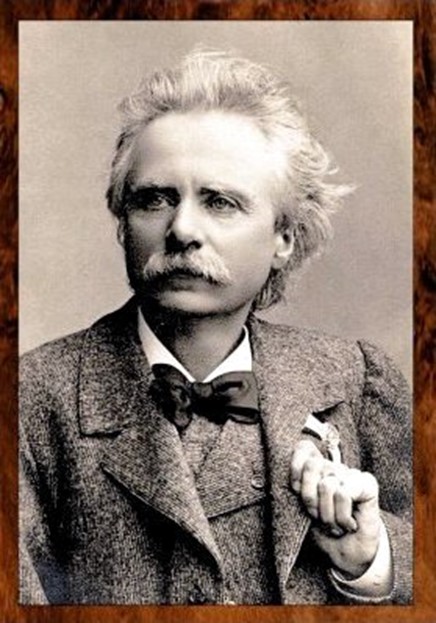

Edward Grieg was a Norwegian composer known for his nationalistic and folk melodies. In Leipzig Conservatory, he was trained under the best pedagogues in Europe such as Ignaz Moscheles and Carl Reinecke. [1] Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Liszt directly influenced his music, thus characterizing the German romantic tradition interposed with national awareness. He has felt the need to create a unique Norwegian style through folk melodies, and some authors had the impression that Grieg’s music reflects the way of life and landscape around him. Says one professor from Norway, “There was an intense and indissoluble relationship between the environment he lived and the music that he created.” He often spent his summer months in a secluded wooden cabin built for him in the midst of the mountains wherein to compose his music. [2]

Lyric pieces (originally “Small Lyric Pieces” or Lyriske smaastykker) is perhaps Grieg’s greatest contribution to the romantic piano literature, with its “melodic charm, rhythmic and harmonic freshness, and national flavor” [3] The 10 volumes present “simple, intimate mood images” that was loved even during his lifetime and gave him the title “The Chopin of the North.” [2] It was published from 1867 to 1901, that saw evolution in style and maturity of compositional writing. You will find the famous selections with descriptive titles such as March of the Trolls, Spring, and Wedding Day at Troldhaugen. Arietta, the first piece in his first book, Op. 12 is a favorite melody. He loved it so much that he used it again at the last lyric piece, Remembrances (Efterklang), this time as a waltz.

The Romantic Style: Three-Voice Texture

In order to fully understand Grieg’s Arietta, we need to talk about the general Romantic style. Composers commonly use the three-voiced texture. In fact, if you look at Songs without Words, No. 1 composed by Mendelssohn earlier, you will find the same texture and even the arpeggio shared by both hands.

Composers seem to be preoccupied with the concept of foreground (melody), middle (filler), and background (bass). [5] This trend did not begin in the Romantic era as we find in Beethoven’s Sonata in C Minor, “Pathetique”, also a three-voice texture, which demands control of the inner voice and projection of the full duration of the top note.

| How to teach Balance and Voicing in a Three-Voice Texture 1. Block chords. This will give the student the awareness to the underlying harmonies. 2. Let the student play the top note of each chord, followed by the rest of the chord in a lower dynamic level, to create a good voicing of the top note. 2. Isolate the voices. Play a combination of two voices. For example, the student can play melody and bass alone, or melody and middle voice. Isolation of voices forces the ear to listen to parts that it normally does no pay attention to. 3. Let the student play the arpeggio notes with one hand (either left hand or right hand), while you play the melody. Work on ensemble and balance. When student is playing with alternating hands, suggest to listen for this smooth harp-like accompaniment. |

The Romantic Style: Rhythm and the Tempo Rubato

The Lyric pieces belongs to a period where music does not strictly follow time. Tempo rubato is loosely defined as the fluctuation around the basic pulse. In a way, it signifies freedom and liberties of the melody in relation to the accompaniment.

“We can and must play in rhythm, but we need not keep strict time whenever our feelings forbid it.” —Constantine von Sternberg

Our job as piano teachers is to help the students make intelligent and tasteful decisions on executing rubato. As John Berger, a violin professor puts it, “genuine rubato comes from a deep knowledge and familiarity with the music…and is strongly associated with the performer’s own musical expression of melodic and phrasal shaping.

| Teaching Strategies for Tempo Rubato in Arietta 1. Practice steady rhythm devoid of rubato. Do rhythmic practice in groups of eighth notes and quarter notes, and eventually in half notes. Rhythmic practice is effective to give the students time to audiate in groups. It will also help solve the problem of hesitation and thinking beyond the bar lines. 2. Suggest relaxation at the end of the phrases, in climax or interesting harmonic changes, and to emphasize short and long durations. |

Achieving Harmonic Lyricism

As we have mentioned earlier, Grieg’s harmonic vocabulary is an assimilation of the late-classical to early-Romantic traditions. One common practice that evolved during this time is the modulation to distantly related keys. [6] In this piece, though the modulation seems to be closely related (e. g. Eb-Cm- Gm-Eb), he modulates by bridging the common tones, usually in the melody. In fact, the melody seems to grow out of harmony. One important thing to note is his treatment of cadences, because they are the basis of the form and structure.

We cannot overlook Grieg’s genius use of chromaticism. Notice his treatment of the bass, in mm. 5-7 and mm. 8-9. What could have perfectly worked out as an Ab (subdominant), he substituted with A half-diminished seventh, to pave the way for a chromatic bass movement. He also used this chromatic voice leading in the inner voice, such as Bb to Cb in mm 1-2. This subtle voice leading suggests a smooth, sweet and unassuming lines. No wonder Arietta has a effortlessly smooth, and lyrical background!

“Alert sensitivity to the balancing of sonorities so that the musical sense of the phrase is not sacrificed to the busy inner activity.” — James Lyke

| Teaching Strategies for Harmonic Lyricism 1. Illustrate the Tonic-Subdominant-Dominant-Tonic (I-IV-V-I) progression. Briefly describe how they relate to phrasing. Ask the student to make decisions how to create longer phrasing based on this concept. 2. Look for interesting harmonic changes in the piece, such as the unexpected A natural in m.6. To emphasize its impact, let the student play the expected Ab chord, then listen to how Grieg made it different. 3. Mark cadences (m10, m12, m20, m22) that concludes large phrases. Ask the student to listen for these points to breathe and take time. 4. Outline the form and look for similar passages or the return of material. Outlining the form is also a useful tool for memorization 5. For longer phrasing, treat common tones as indicators to continue the melodic line. |

Achieving Melodic Lyricism

Arietta, which means “little aria” is an Italian term that means “an elaborate melody sung by a single voice that is accompanied by instruments. Arias are part of a larger work called opera or oratorio, and so ariettas are simpler versions of that. Talking about simple, the seemingly unassuming melody of Arietta could fool anyone easily because it looks easy. After all, they are just repeated notes. However, a careful look will show that the whole melody is actually played by fingers four and five. This is not an easy task for these outer and weaker fingers, especially if you want to achieve a legato sound.

One important aspect of this “simple” melody is the antecedent and consequence or the question and answer. This melody is linear and uses adjunct or step-wise motion, abundant in common tones.

| How to Teach Melodic Lyricism 1. Ask the student to be familiar with the top line melody through singing, listening, and audiation. Have student play the bass line while singing the melody and suggest taking note of the contour and phrasing. 2. Experiment on different fingering on the melody. Suggest playing it even with the left hand. Use fingers (4-3-2-3) or other permutations to avoid over-familiarization to force the ear to listen to the line. Be aware of this smooth line when playing the finger four and five on the melody. 3. Have the student aim for graduated dynamics of repeated notes by playing in different areas of a single key (edge of key to inner portion). Use appropriate gestures such as higher wrist. Let the student listen to the underlying harmony as a guide. 4. Have the student practice without the pedal and depend on finger legato. Measure 11 requres a smooth transition to the second beat. Be careful that there is no hiccup here, or a detachment from Ab (finger five) to B (finger three). |

Conclusion

Grieg’s Arietta, a piece for early to late-intermediate level, is a wonderful introduction to the characteristics of the Romantic piano literature. A wholistic approach and incorporation or theoretical concepts will aid the student to make intelligent and independent decisions regarding phrasing, musicianship, and production of tone.

Bibliography

1 Kode Art Museum and Composer Homes. Edvard Grieg Museum. https://griegmuseum.no/en/about-grieg#:~:text=The%20first%20time%20was%20a,had%20the%20greatest%20respect%20for.

2 Harald Herresthal. Edvard Grieg. http://www.mnc.net/norway/grieg.htm. Accessed October 28, 2020.

3 Finn Benestad and Dag. Schejelderup. Edvard Grieg The Man and the Artist. University of Nebraska Press. 1988.

4 Barela, Margaret M., and Paul J. Althouse. 2002. “Guide to Records: Grieg.” American Record Guide 65 (4): 109.

5 James Lyke, Geoffrey Haydon, Catherine Rollin. Creative Pa p 211

6 John Horton. Grieg. JM Dent & Sons LTD London. 1974

7 Lyric Pieces, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lyric_Pieces

8 Allysia, “Grieg’s Arietta Tutorial”, Piano TV: March 27, 2019

9 Shirley Kirsten, (HD) Piano Tutorial, Edvard Grieg Arietta Op. 12, No. 1, March 12, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaYOjc7sRpU&feature=share

10 Arietta, Collins Dictionary, 2019. Penguin Random House LLC.

11https://www.collinsdictionary.com/us/dictionary/english/arietta#:~:text=a%20short%20relatively%20uncomplicated%20aria,from%20Italian%2C%20diminutive%20of%20aria

12 Betsy Schwarm, Lyric Pieces (Encyclopedia Brittanica, 2013). Accessed on October 28, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Lyric-Pieces

13 Layne Vanderbeek, “Harmonic Syntax in Edvard Grieg’s Lyric Pieces” (D.M.A., State University of New York, 2020), https://search.proquest.com/docview/2416928438?pq-origsite=summon

Thank you for sharing your research on this Grieg’s beautiful selection and your very thoughtful teaching strategies. I can particularly benefit from the approach to rubato and from the voicing exercises! 🙂

LikeLike

Your performance of this piece was beautiful! I particularly enjoyed your explanation of the chromatic harmonies.

LikeLike